The life of a Gnani, a mystic or a Siddhapurusha is never merely a process of time, a chronological sequence of events as it happens in most of our lives. It is even more so in the case of Swami Gnanananda. One can never say with confidence that one has understood his life or successfully bring it into the confines of history. Any attempt at writing about him is bound to be incomplete; for one thing he ‘has lived beyond the normal span of life — more than one and a half centuries’ by general estimate; for another he has always discouraged any inquisitiveness about the trappings of the body and mind, about his age and ‘purvasrama’ or life prior to renunciation. Mark, for instance a cryptic reply by the Swami recorded by a lady devotee who had heard that Swami has lived more than 150 years, “How old are you Swami?” asks a small girl. “Sixteen” quips the Swami.

However incomprehensible and impossible, it is natural that the finite aspires to know the Infinite. Thus, to the queries of pestering and pertinacious devotees, the Swami has given answers now and then: in a highly metaphoric and symbolic language, giving clues and hints, leaving the devotees to guess the rest. To naive questions about his age, which has always been a point of wonder for devotees, at home and abroad, the Swami has given evasive replies; for in the renowned Hindu spiritual tradition, the body, with its physical and vital aspects, has itself been regarded, on the one hand, as immaterial and on the other as ‘the temple of the Divine. Thus its ageing process is ‘known to have been conquered by certain yogic disciplines’ and powers by many rishis. The Swami has consistently answered his disciples that they would do well to direct their efforts and Bhakti towards realizing the Higher Self which is the Ultimate Reality, instead of looking back and frittering away their energy in such futile questions about his age and other externals.

The Swami’s previous history is shrouded in mystery for everyone. Swami Gnanananda himself was always reserved when speaking of his former life. ‘What was his age?’ was the most natural question. “Most people said” writes Swami Abhishiktananda, “that he was a hundred and twenty years old. Others, by astrological calculation, made him out to be one hundred and fifty three. But how could one believe he was so old when he was still so alert, walked so briskly, and drew his own water from the well for his morning bath? He enjoyed good health, directed every smallest detail of the ashram life, and supervised any new building project. His face was smooth and without a trace of a wrinkle. Looking at him one could hardly have believed he was yet seventy.”

Based on various anecdotes and a few casual remarks of the Swami himself it is learnt that the advent of Swami Gnanananda must have been sometime early in the last century. It is believed by many of his devotees that he was born in the month of ‘Thai’ of Tamil calendar (January) with the birth star of ‘Kritika’, in the village of Mangalapuri in the North Kanara District of Karnataka State, to an orthodox Brahmin couple, Sri Venkoba Ganapati and Srimathi Sakku Bai. Here is one instance of his humorously describing his parentage: “Swami was born in Mangalapuri, at least that is what people believe (with the curious note of impersonality and wit in this account).

He was named Subrahmanyam. The religious function of his investiture with the sacred thread and initiation into the Gayatri Mantra, ‘Upanayana’ was performed by his parents when he was seven. He seems to have left his house at a very early age, perhaps when he was eleven or twelve. Was it the urge to know the Self that drove him to that ancient and famous pilgrim centre in ‘Maharashtra State, Pandharpur, where he offered worship to Lord Panduranga? One does not know. It was to this hallowed spot, however, that he was led by a divine light and it was there that the disciple heard the call of the guru.’

One night when he was sleeping in a mandap on a sand dune on the banks of the sacred river Chandrabhaga, he was awakened by an old brahmin who expressed his appreciation of the boy’s spiritual quest and informed him that a saint destined to be his guru “was right there at Pandharpur and that he could join him”. Subrahmanyam was disappointed when this strange messenger who had gone for his bath in the river failed to come back. Slowly realising that it was the Lord himself who had guided him in this mysterious manner, he made enquiries in the morning and learnt that Sri Swami Sivaratna Giri, of Jyotirmutt, one of the four mutts established by Adi Sankara himself was camping in the city. Driven by his own urge to find his guru and attracted by the grace of the seer, the boy eagerly ran up to Sri Swami Sivaratna Giri and offered salutations to him in the traditional manner and stood visibly moved in his august presence.

It is significant that this is one of the very few events of his life on which the Swami chose to comment.

More important still is the way he was moved to tears by Bhakti,’ for all his being a gnani, whenever he referred to this incident. References to his master by the Swami were rare and invariably brief and even in those precious moments, emotion surged in his heart and obstructed the flow of words. It is appropriate to recall here what the Swami had to say describing the most important event of his life when he offered himself to his guru: “This world is a river in spate with strong currents of strife, sorrow and agony threatening to engulf us. But good fortune it was that rescued me from these dangers and seated me firmly on the effulgent rock of Sivaratna, His Grace enveloped and took full possession of me in time before I was drowned. My master was waiting for me under a tree on the shore and the powerful glow of his eyes drew me automatically to him like a magnet.” It was as if the guru and the disciple were waiting for each other. Grace brought them together. It was a spontaneous and absolute surrender.

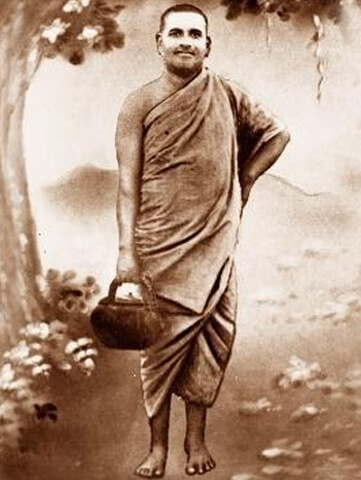

It is said that he who chooses the Divine has already been chosen by the Divine. Sri Swami Sivaratna Giri acknowledged his profound devotion by commanding him, “Keep my ‘Kamandalu’ (water pot) ever filled with ‘theertha’ (holy water)” and thus bid him do intimate personal service. Soon impressed by the boy’s burning vairagya’ or dispassion, his ‘prapanchavirakthi’, astonishing indifference to the material world, his inborn fascination for spiritual life and intense aspiration for Self-Realisation, Sri Swami Sivaratna Giri accepted him as his disciple and named him ‘Pragnana Brahmachari’.

Swami then followed his guru, Sri Swami Sivaratna Giri, like a shadow and derived great delight in serving him. There is a valuable reference to the kind of absolute devotion with which he served his master. Partly in his characteristic vein of irony and partly seriously, Swami used to chide his devotees whenever they were found to be lax or indifferent in their work and tell them how he, as a disciple, would do all the menial duties to his master with great love and devotion. Under the guidance of his guru, the Swami not only became proficient in ‘Ashtanga Yoga’ but also learnt all the texts of Hindu scriptures. Constantly engaged in reflection and contemplation of the Upanishadic truths, the Swami was steeped in intense spiritual sadhana. The years spent by him under the tutelage of his Guru were doubtless. replete with scintillating episodes of joy and experience.

When our Swami was about thirty-nine years old, Swami Sivaratna Giri indicated to his disciples his intention to shed his mortal frame. Shortly thereafter, ‘Pragnana Brahmachari’ was initiated by his guru in the traditional manner; into the ‘Giri’ order of Jyotir Mutt and was given the’ ‘Diksha Nama’ or monastic name of ‘Sri Gnanananda Giri’ and the ‘Danda’ (staff), ‘Kamandalu’ (water pot) and saffron robes. Sometime later, Swami Sivaratna Giri attained Mahasamadhi as forecast by him, in his eighty-first year, on the full-moon day in the month of ‘Chitra’ (April-May). The anniversary of this event’ is celebrated even today as his commemoration day at Tapovanam, Attiyampatti and other ashrams established by Swami Gnanananda.

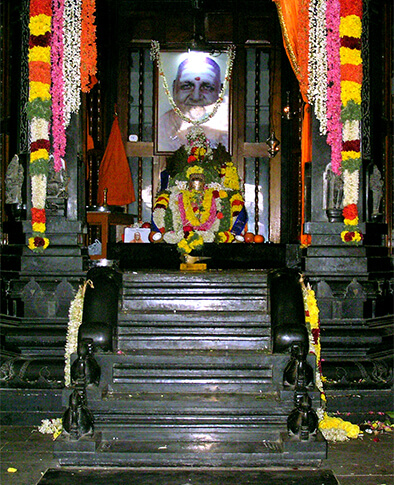

THE Swami’s life size sila vigraha which is installed at Tapovanam was two years in the making and was arranged to be sculpted in Bangalore by a devotee. It is carved out, of a single monolithic black stone and was etched referring some of his photographs. When it was brought to Tapovanam and it was the Swami’s wish that it should be installed there — the image was placed in a niche in the northern wall of the Bhajana Hall on the Chithra Pournami day in 1959. The devotees coming to the ashram would make their pranams to the idol and place their offerings before it in prayerful worship.

The Swami had a brick wall built in front of the vigraha concealing it from view for quite some time. Subsequently he had built a small mandapam with four pillars and the sila was installed there on ‘Thai Krithika’. A garbhagriha and later a manimandapa were also built. Over a period of time the idol has acquired a serene dignity and loveliness. Devotees do not fail to note how angularities have disappeared and the features have acquired nobility and grace.

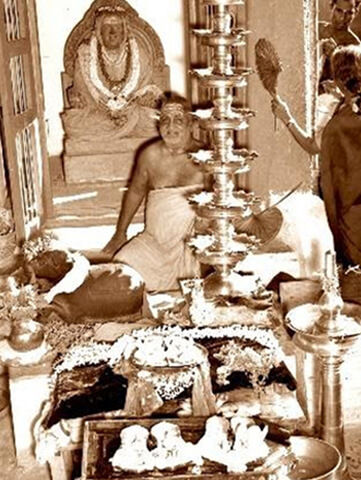

On all important occasions the Swami would sit in the manimandapa, a little ahead of the idol to enable the throng of devotees to perform the paduka puja, thus surcharging the atmosphere with a still and intense spiritual feeling.

Devotees who look at It feel an invisible strength coursing through them and a harmony which spells peace, supreme confidence and inner silence.; a calmness that suggests the stilling of mental agitations, nudging them to deep contemplation. To the ardent devotee, It is the gateway to the blessed Essence of things; Its presence bespeaks of an inexhaustible joy, life-giving courage and plenitude.

Undoubtedly it was the Swami’s God-like concern and compassion for suffering humanity that must have prompted him to agree to his idol being consecrated for worship at the ashram; he must have intuitively divined the anguish of his devotees when they would no longer see him in his physical form. He must have thought that his image might somewhat assuage their grief.

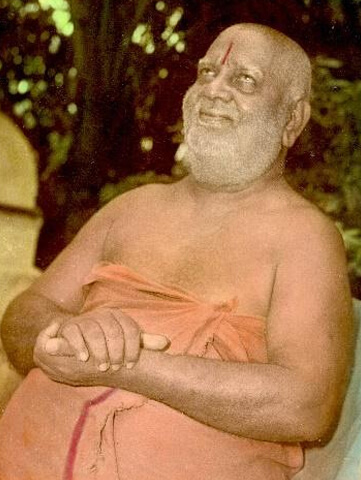

Swami's simplicity, sweet amiability and his knack of being at home with everyone he talked to, be he a saint or sinner, merits special mention. Any one meeting him for the first time would feel completely at ease. All devotees found in swami a real refuge from the tragedies and disappointments of life.

On association with Swami, one would be drawn to absolute conviction that Swami would always be watchful of their welfare, and that all one needs to do is just practice "absolute surrender" A gesture from the Swami, a kind enquiry, a smile would leave them spell bound and dissolve all their discomforts. Devotee's of Swami Gnanananda basked in the sunshine of Swami's grace and filled themselves with his overwhelming mercy. Swami drew all his devotees to his fold by his grace and awakened in them an intense desire for the life of the spirit. To all of them, he was a "Karunamurthy".

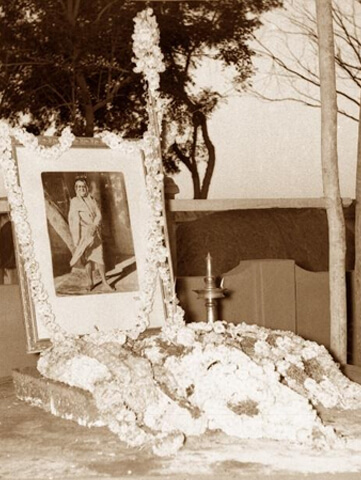

Swami attained Mahasamadhi in the year 1974 (January). While Swami’s idol at Manimandapam is itself the symbol of the Swami as Dakshinamurti, the Mahalinga consecrated on top of Swami’s Samadhi per his instructions (to devotees well before his Samadhi) is the symbol of God’s coming into His creation and equally the symbol of the creatures passing, his departure into God. The Shivalinga stands between form and non-form, rupa and arupa, between manifestation and what can never be manifested.” The Swami had expressed a desire that the deepastamba — a column of lights’— which stood in front of the idol should be moved ahead a little further to a point from which one can pay obeisance to both the idol at Manimandapam and the Mahalinga at the samadhi.

The column of lights is the symbol of the Knowable, the self-luminous Brahman which is the inmost Self of everything, the Light even of lights, eulogised in the Gita as ‘Jyotisharriapi Tajjyotih’, By Its light, Its radiance, everything is lighted, illumined .

The Swami is wholly present in these signs “which are utterly ‘beyond’; yet at the same time and for that very reason most intimately within, the absolute of both transcendence and immanence”. His transcendence is the very source of immanence; “transcendence and immanence being no more than two of man’s words by which he tries to indicate simultaneously the beyondness and the withinness of the supreme mystery, both the rupa and the arupa of Being.